COVID cold chain

- PostedPublished 12 December 2020

Pandemic-busting vaccines need those working in temperature controlled transport and cold chain to bring their A-game

In 2020 the word ‘unprecedented’ has been used with unprecedented frequency and now we have the unprecedented challenge of distributing vast volumes of COVID-19 vaccines around the world at strictly controlled temperatures of less than -70°C.

As a result, those working in transport refrigeration and the cold chain are probably about to get very busy, especially those with a reputation for knowing what they are doing and doing it well.

The first COVID-19 vaccine approved for human use, developed by Pfizer and BioNTech, is also one of the most difficult to transport and store due to the fact it only remains stable below -70°C.

Others not yet approved when we went to press include the Moderna vaccine, which must be kept at -20°C and the Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine, which can survive in standard refrigerated conditions.

Pfizer alone plans to distribute 50 million COVID-19 vaccines before the end of this year and another 1.3 billion in 2021.

The company’s production facilities in Michigan and Belgium have ultra-low temperature freezers that can keep the vaccines fresh for up to six months.

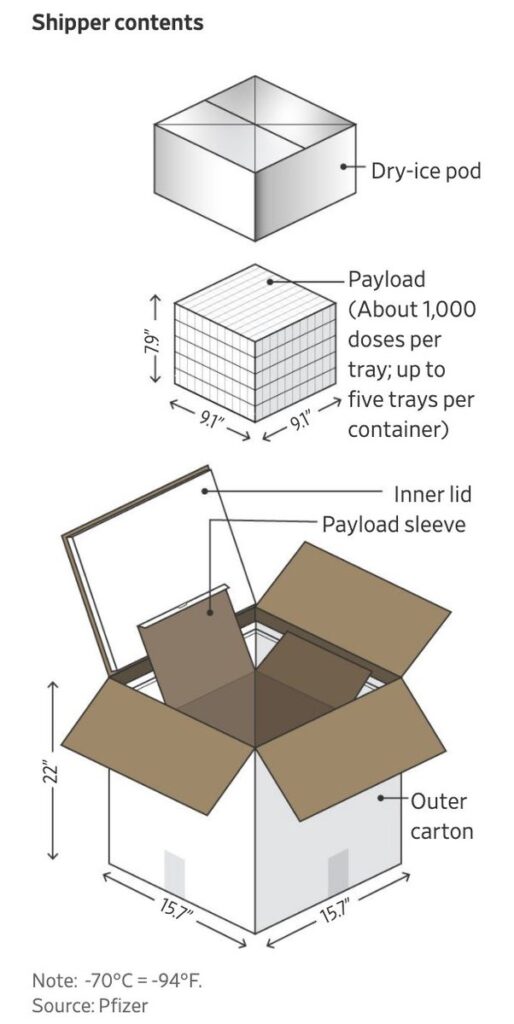

From there, insulated shipping boxes carrying up to 5000 doses of COVID-19 vaccine are packed with dry ice and can keep the vaccine viable for up to 15 days.

The Pfizer vaccine can also last up to five days in a regular refrigerator, for example at clinics where they are likely to be used quickly.

Critical to all this is the caveat ‘up to’. It assumes the vaccines have been handled correctly and not subjected to fluctuations in temperature, which can happen when they are transferred between different modes of transport.

Even though the Moderna and Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccines look easier to handle due to their more conventional safe temperature ranges, this arguably makes them even more vulnerable to what is known as ‘temperature abuse’.

In an interview with ABC News, VASA director and Australian Food Cold Chain Council (AFCCC) chair Mark Mitchell explained that careful handling would save thousands of vaccines from being wasted.

He identified the control points where a temperature-controlled load changes custody (such as being transferred between two vehicles or handled through a distribution centre) as “where temperature abuse occurs”.

Drawing a parallel to the food industry in Australia, Mitchell said “a quarter of the fresh produce that leaves the farm gate doesn’t make it to the supermarket due to a break in the cold chain”.

“Most of the reason that happens is because of poor handling … We struggle here in Australia to keep our cold chain totally compliant.”

Compounding this risk are the sheer number of vaccines that will be hitting the roads, having been air-freighted in from overseas, and the fact no vaccines currently used in Australasia have to be kept below 70°C.

Also, the first shipments of these vaccines will likely be coming from the depths of winter in Michigan and Belgium to the heat of a southern hemisphere summer.

As AFCCC and Refrigerants Australia executive director Greg Picker put it, “the challenge is absolutely massive”.

“Your average pharmacist and medical centre (in Australasia) has never seen -70°C in their lives.”

The air freight matter comes with its own bumps in the road, not least the fact that the Civil Aviation Safety Authority classifies the dry ice used to keep Pfizer’s vaccines cool under dangerous goods.

Also, for the insulated boxes to keep the vaccines viable for the quoted 15 days they must be refilled with dry ice at least twice, which Mitchell saw as a “bloody tricky exercise” that would require those in the COVID-19 vaccine cold chain to be specially trained.

Pfizer itself recommends that to maintain insulation, the special boxes should not be opened more than twice a day.

And, even when refilling with fresh dry ice, they should not be left open for more than one minute otherwise the vaccines need to be transferred to a regular refrigerator and used within five days.

Rushing the refilling job is hazardous as breathing the carbon dioxide vapour from dry ice can lead to asphyxiation and touching the dry ice can cause frostbite.

A sudden spike in demand for dry ice could cause problems elsewhere in the economy as the product is usually supplied on demand, but Australasia’s largest dry ice suppliers BOC and Air Liquide have both issued statements of confidence that they will be ready.

Australia’s geography and smattering of small-population communities could also prove challenging for the Pfizer vaccine as the standard thermal shipping boxes contain so many doses, meaning one of the alternatives that can be distributed using regular refrigerated transport might end up being adopted for regional and remote areas, if and when they are approved.

When the vaccines are rolled out in Australasia, refrigerated trucks and containers will have to be kept operating flawlessly, with accurate and reliable temperature monitoring plus robust procedures and training to make sure the COVID cold chain remains unbroken.

Australian Refrigeration Council CEO Glenn Evans said the HVAC&R sector – including many VASA members – will play a vital role in the distribution of vaccines.

“We’d be in a whole lot of trouble without the men and women of the refrigeration and air-conditioning sector,” he said.

- CategoriesIn SightGlass

- TagsCold chain, COVID-19, pandemic, refrigerated transport, SightGlass News Issue 22, transport, transport refrigeration, Vaccines