Hyundai Kona Electric review

- PostedPublished 30 June 2019

SightGlass News editor Haitham Razagui bowled over by Kona Electric

During almost a decade working as a motoring journalist, I have driven a different brand new car every week.

As such, it takes a lot to impress me and the Hyundai Kona Electric did just that.

Kona vs. range anxiety

Still harbouring anxieties from a range-sapping motorway drive experience I had with a Mitsubishi i-MiEV in 2011 (see Page 3), it was with trepidation that I embarked on my first trips with the Kona.

This was because my schedule required me to drive immediately to VASA HQ on the Gold Coast after collecting the Kona from a depot in Brisbane, then drive home to the Sunshine Coast.

Without the opportunity to recharge at home that night, I would then have to drive back to Brisbane for a breakfast meeting first thing the next day.

I collected the Kona with a full battery and 468km reported on the range gauge, yet my 48km motorway drive to VASA HQ was completed with 434km remaining.

Having used just 34km of range, the Kona had consumed less electricity to cover this distance than the its own calculations had predicted. This, on the kind of motorway journey that would have depleted much of that old i-MiEV’s energy.

I was full of confidence that the 140km drive home that night would be completed with plenty of range to spare for my Brisbane-bound leg the next day.

After covering more than 190km on my first day with the Kona, I arrived home with 295km of remaining range. Plenty to get me to Brisbane and back again.

There would even be enough for another one-way trip to Brisbane if I was feeling brave enough.

The real-world range of this car was starting to look like more than 485km, even on the kind of motorway driving that tends to sap EV batteries far quicker than stop-start urban work.

Charge!

By coincidence, beside the venue of my breakfast meeting in Brisbane was a pair of Yurika rapid chargers that had been in action since February 2018.

It was simple to hook up the Kona and my visit took place while recharges were still free (an introductory scheme that expires on June 30, 2019).

On my return 72 minutes later, the rapid charger had restored the Kona’s battery to 95 per cent and the dashboard display reported that my range was now 456km.

During the rest of my week with the Kona I plugged it in three more times for quick top-ups. Each time, this was at public Tesla chargers (not Superchargers) that worked perfectly well with the Kona.

I found these Tesla units at local shopping centres and even Australia Zoo. Compared with petrol station stops, plugging in while getting groceries or enjoying a family day out was a pleasure.

Conveniently, I found local solar inverter manufacturer Latronics Sunpower also provided a Tesla charger for public use. As with the shopping centre and zoo chargers, there was no cost to use the charger but the energy flow was pretty slow, taking around two hours to add 50km of range.

Living with the Kona and lacking a charger at home, I found myself exploiting these top-up opportunities whenever they fell into my daily activities. I wouldn’t usually drive 450km in a week, so would rarely have to take the Kona for a full charge if I owned one.

That said, I’d install a 7.4kW charger in my garage if I did own an EV. As I work from home a lot, I could charge the car during the day using solar energy and recoup the cost of the panels more quickly.

Range anxiety, kind of

I had another chance to sample the Kona several weeks later, for a trip to Byron Bay so I could attend the Northern Rivers EV Forum.

Surprisingly, given the fact an EV Forum was being held here, charging infrastructure in the Byron Bay area left a lot to be desired.

After driving the Hyundai from Brisbane to my accommodation in Bangalow, plus a few trips between there and Byron during my three days in the area, there wasn’t enough remaining range to get home to the Sunshine Coast.

I decided that a return to the Yurika rapid charger in Brisbane was my only option. But getting there would be a squeeze.

Happily, I arrived at the charger with almost 50km to spare and it took just an hour to restore the Kona’s battery to 80 per cent and almost 400km of range.

It was a good opportunity to stretch my legs and get some fresh air to break the three-hour journey.

But how does it drive?

Let’s quickly bust the myth that electric cars are boring and slow.

If anything, Hyundai could have endowed the Kona Electric with a lot less power and still delivered an excellent driving experience. To me, it easily felt overcome by its own performance.

From any legal road speed, acceleration response from the Kona Electric is instant, assertive and seamless. It’s grunty enough to push you back in the seat and the power piles on relentlessly as there’s no pause to change gears.

To get even close to this experience with a combustion engine you’d need a V12 and the most seamless automatic transmission on Earth. A Rolls-Royce perhaps?

Maybe this slick performance is all you need to help justify the hefty $24K price premium over a top-spec petrol Kona. I have to admit it won me over big time.

The nippy, fun nature of the combustion Kona is carried through and the extra zip and zing of the electric drivetrain adds a charming point-and-squirt character to the car when zipping into gaps in traffic.

Being powerful and front-drive, there are compromises that you don’t experience in turbo-petrol Konas with all-wheel-drive.

I also found braking to be a little abrupt and never totally got used to it, but I did enjoy the variable regenerative braking that is controlled via the steering wheel mounted paddles.

Although it sounds unintuitive, I regularly used the Kona’s paddles in a similar way to changing down a gear or two for some engine braking when going down hills.

Compared with a petrol Kona there are some minor interior differences, such as the push-button gear selector and large storage area beneath the centre console. There’s also the all-digital instrument panel.

The main thing, though, is how much better the Kona Electric is to drive than almost any petrol-powered small SUV.

What? This EV uses R134a?

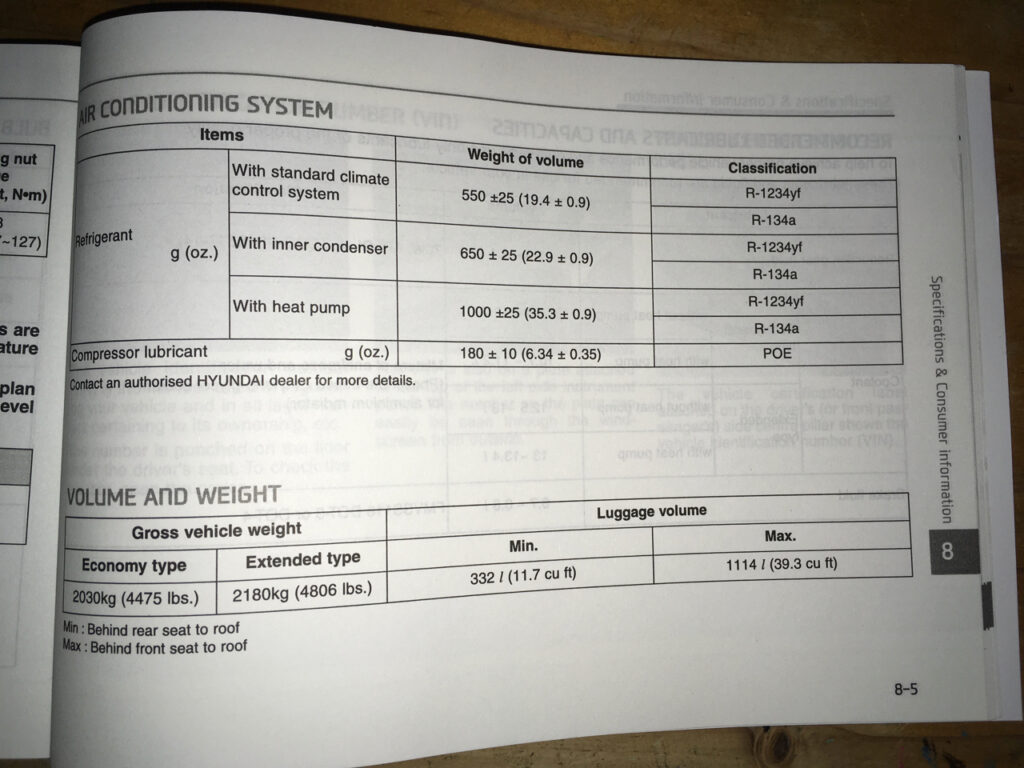

I was disappointed that the Kona’s J639 label said R134a rather than R1234yf. On a hi-tech eco car, what hypocrisy is this?

It seems, like so many other car manufacturers, that Hyundai is exploiting Australia’s lack of legislated requirement for cars to use alternative refrigerants.

After all, the Kona’s glovebox guide clearly mentions both R134a and R1234yf.

I also managed to deduce from the J639 label’s indicated 650g charge weight that Australian-delivered Konas have the inner condenser climate system.

This I take to mean the AC has a reverse-cycle mode for heating rather than the fully fledged heat pump system offered in colder climates that, according to the glovebox guide, requires a 1kg refrigerant charge.

Electric Konas equipped with a heat pump also require another half-litre of glycol coolant over those without.

Glycol you say?

Plenty of plumbing is on show beneath the Kona Electric’s bonnet, including the point where the refrigerant circuit goes into a heat exchanger that regulates the temperature of glycol used for thermal management in the battery and, presumably, other drivetrain components.

Hyundai has clearly designed for this component to be easily removed for repair or replacement. With regular temperature fluctuations plus refrigerant and glycol passing through, it’ll surely need looking after at some point.

For a fascinating level of detail on the Kona’s thermal management system, see http://tinyurl.com/KonaThermal

What about maintenance?

The Kona Electric’s servicing intervals are a pretty standard 12 months or 15,000km and the glovebox guide covers the first eight years or 120,000km.

It advises to “inspect coolant level and for leaks every day” but apart from that, the first coolant inspection is recommended after 60,000km or 48 months, with subsequent checks every 30,000km or 24 months.

The first coolant replacement comes at 210,000km or 10 years, after which it must be replaced every 30,000km or two years.

Reduction gear fluid must be inspected at 48 months/60,000km and 96 months/120,000km but no replacement is required during this timeframe. In fact, everything in the service schedule is labelled ‘inspect’ rather than ‘replace’ for the first 120,000km.

The air-conditioning compressor, refrigerant and cabin filter are among the items that must be inspected at every service interval, along with battery condition, brake systems and steering/suspension/chassis.

At a Hyundai dealership, each of the first five services cost $165 for the Kona Electric, which is covered by the brand’s general five-year/unlimited km warranty.

Separately, the battery warranty is eight years or 160,000km.

Opinion: Editor’s EV back story

By Haitham Razagui

SightGlass News Editor

MY FIRST experience of an electric car was the Mitsubishi i-MiEV in 2011.

Colleagues had jury-rigged a 15A extension cord so we could charge it outside the newsroom where I worked.

One of them ended up running out of battery just as he arrived at work, having to push this pioneering Mitsubishi the final three metres of its journey so that our improvised charging cable could reach.

I was tasked with returning the i-MiEV back to Mitsubishi once our test drive period had ended.

The plan was for me to drive it home after work and return it to the manufacturer first thing the next day.

However, I was perhaps a little too obliging when a curious neighbour asked me to take him for an evening drive in this futuristic little car.

Keen to dispel the perception that electric cars would be slow, part of the drive route with my neighbour took in some motorway miles, with a swift punch of acceleration up the on-ramp.

I then learned that travelling at motorway speeds resulted in a rapid recalibration of the i-MiEV’s battery range display.

Happily, much of my journey back to Mitsubishi the next morning was downhill, relieving some of my intense range anxiety as regenerative braking earned me enough spare kilometres to get to my destination without mishap.

Shortly afterward, I was lucky enough to drive the original Tesla Roadster.

My drive of the Roadster in thick Melbourne drizzle was brief but vividly memorable, as you’d expect from a pivotal piece of automotive history costing $260,000.

Ever since, electric cars with anxiety-busting battery range have remained well above the $100,000 barrier.

That is, until Hyundai launched the Kona Electric with a 450km battery range and $60,000 starting price earlier this year. And now, Tesla’s long-awaited Model 3 is available from $66,000.

What these cars represent is the end to what feels like an eternity in which the only pure-electric cars available in Australia were the quirky, costly BMW i3 and Tesla‘s even more expensive Model S and Model X.

In 2018 things got a bit more affordable with the arrival of Renault’s Zoe (which I first drove back in 2013 on the global launch) and the Hyundai Ioniq.

But for anything other than urban work, these models still came with an aroma of range anxiety.

I sensed a shift when Hyundai launched the Kona Electric, which at the time of its launch in March was literally miles ahead of other sub-$100K EVs. The next most affordable model with this kind of range was the Jaguar I-Pace, costing a minimum of $119,000 before on-road costs and options.

That said, some wind was no doubt taken from of the Kona’s sails when Tesla confirmed Australian pricing and availability for the rear-drive version of its Model 3 with 460km of range. It is without doubt more spacious and desirable than the Kona, for not much more money.

Kia’s e-Niro, essentially a slightly larger model based on the Kona’s technology, will launch at the 2020 Australian Open in January. But like the Kona, overseas pricing for this model is only slightly lower than that of an entry-level Model 3.

Having driven the stunning Model S and heard from trusted sources that the Model 3 is even better, I’d have a hard time going for a Kona or e-Niro over the Tesla.

The only thing holding me back from coming to this conclusion was the impending arrival of the Volkswagen ID.3, but news that the Australian arrival of this car is delayed until 2022 puts the Model 3 back into pole position.

The new Leaf will arrive in August with a $49K opening ticket but I’d rather pay more for the additional range offered by a Hyundai, Kia or Tesla.

I also have doubts over whether Nissan has moved its EV drivetrain forward enough for the second-generation model and there is no clarity over whether the upgraded Leaf e+ model will be offered here with its superior 458km range.

But from here, long-range EVs will only become more affordable.

Opinion: EVerything old is new again

By Ian Stangroome

VASA President

DURING the lead up to the recent Australian Federal election which, as you well know, delivered an outcome that most weren’t expecting, there was much discussion and debate about the greater use of renewable energies and, in particular, the push for increased take-up of electric vehicles on Australia’s roads.

Most of the publicised discussion surrounding electric vehicle technology revolved around the initial cost of the vehicles, the travelling distance and how long it takes for an electric vehicle battery to be recharged.

Now, while the outcome of the election may have been a surprise, what shouldn’t be a surprise is the ever-growing community concern of the state of the environment, and the urge to use alternative renewable energies.

While many in the community believe that electric vehicle technology is innovative and new, it’s very much a situation of “back to the future.”

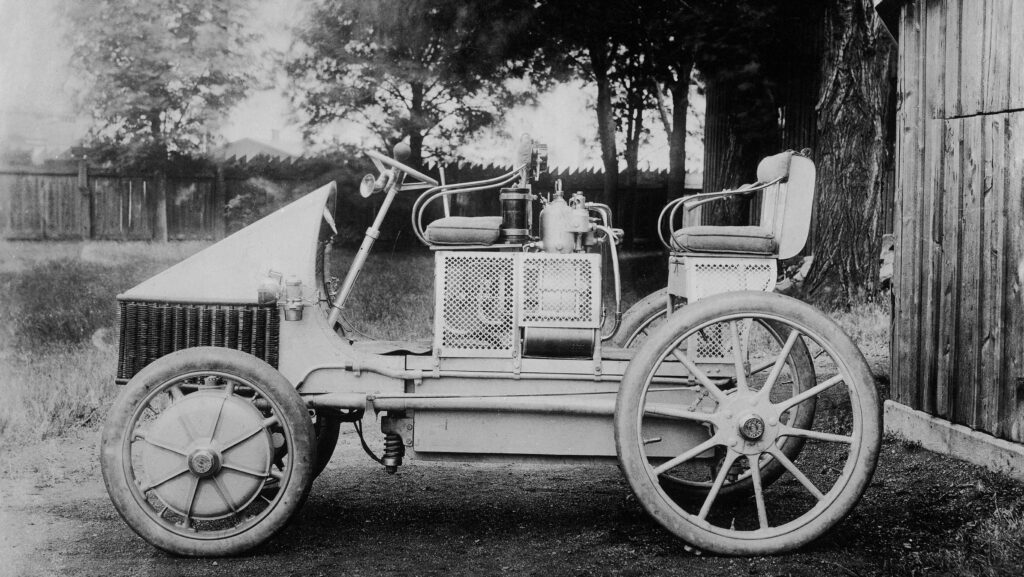

Depending on which sources you care to refer to, the first electric vehicle was invented in the 1830’s, in the form of a primitive carriage powered by a non-rechargeable battery.

Research progressed over the next 20 years until 1859 when the rechargeable lead acid battery was invented, and then in 1891 the first practical electric automobile was built in the United States.

In 1897 the first electric taxis went into service in New York City, and the uptake of electric vehicles was such that by 1900 electric automobiles accounted for approximately 30% of all the vehicles on the streets of Chicago, New York City and Boston.

Many of the electric vehicles were driven by women, as they didn’t have to concern themselves with winding a crank handle, and the duration of their journeys were often very short which suited the available battery capacity of the time.

Consequently, the battery charge was replenished via a charging station in the vehicle owner’s garage. What a novel idea!

Henry Ford’s introduction of the mass-produced Model T vehicle initiated the decline of electric vehicles.

Throughout the 1920s, electric vehicles became progressively less viable compared with combustion engine vehicles that, at the time, were more powerful and could travel further on a tank of fuel, which had become ever more available and affordable.

Since the 1970s, leading up to the era of the ‘fuel crisis’, interest in alternative energy sources to power our motor vehicles has been steadily on the increase.

I recall reading, nearly 40 years ago, about Mercedes Benz’s research into hydrogen fuel. That research and development continues today, having gained the interest of other manufacturers.

Despite this, it remains undoubted that electric vehicles are starting to gain traction (pardon the pun) and will become a major portion of our car parc again in even greater numbers.

They may eventually make up the majority of the vehicle fleet, subject to the introduction of alternative commercially viable technologies.

Either way, our industry is about to undergo a massive change. It’s an exciting and interesting drawcard for new people to enter the industry and for existing participants to take on new challenges.

It stands to reason that whatever your role is in the automotive industry, you will be affected by these new, or reintroduced if you like, technologies and should prepare yourself for them.

Also imperative is that you identify the opportunities that are becoming available to you as a technician or a business owner and seize upon them with the greatest of vigour.

It’s time to get to know what may be the unknown for you.

On that may I leave you with the words ‘Semper Vivus’, which translates to ‘Always Alive’ and the name Ferdinand Porsche dedicated to the dual energy source vehicle he invented while working for Ludwig Lohner in about 1900.

The first hybrid? Who would have thought?

- CategoriesIn SightGlass

- Tagselectric vehicles, EV, SightGlass News Issue 17