Ionocaloric cooling: The end of refrigerants?

- PostedPublished 30 March 2023

A new approach to refrigeration known as ionocaloric cooling takes advantage of how heat is stored when a material changes from a solid to a liquid and could spell the end of refrigerants as we know them.

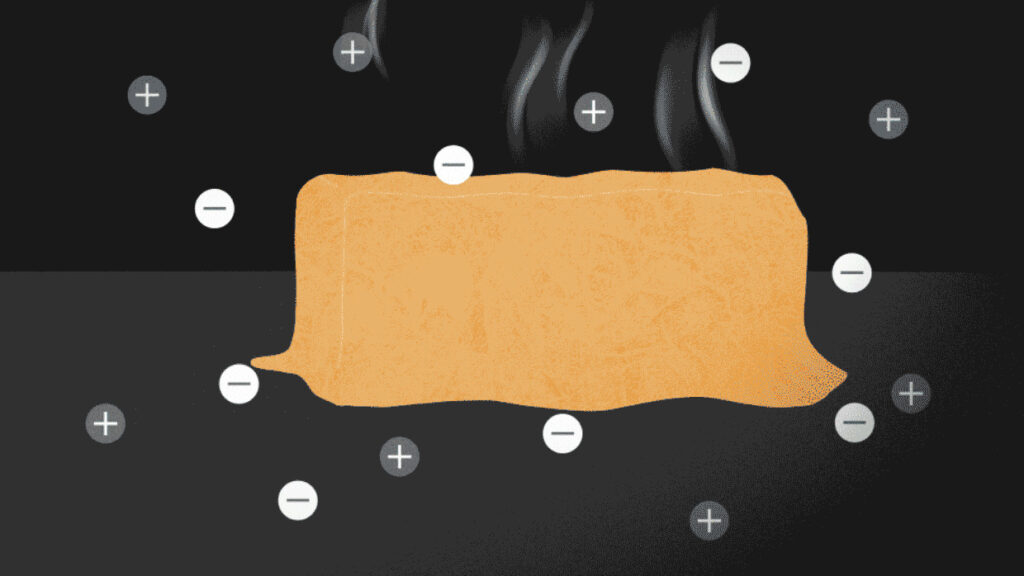

When a material melts it absorbs heat from its surroundings, when it solidifies it releases heat.

In the ionocaloric method – developed at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory – when current is added to the material, ions flow and change the material from a solid to a liquid, absorbing heat from the environment.

When the process is reversed and ions removed, the material solidifies (crystallises), releasing heat.

Ionocaloric cooling could one day supersede vapour compression systems, helping to reduce the reliance on refrigerant gases and the risk of them escaping to atmosphere.

Experiments at the Berkeley Lab used a salt made with iodine and sodium alongside ethylene carbonate solvent.

This demonstrated a temperature change of 25ºC using electrical inputs of less than one volt, a promising performance result when compared to caloric tech such as magnetism, pressure, stretching and other methods of manipulating solid materials so that they absorb or release heat.

It is seen as imperative that cleaner refrigeration methods are found in order to meet global climate change agreements, such as the Kigali Amendment that aims to reduce the production of HFCs by 80 per cent in the next 25 years.

Berkeley Labs researchers Lilley and Ravi Prasher have calculated that ionocaloric cooling has the potential to exceed the efficiency of gaseous refrigerants.

“There’s potential to have refrigerants that are not just GWP-zero, but GWP-negative,” Lilley said.

“Using a material like ethylene carbonate could actually be carbon-negative, because you produce it by using carbon dioxide as an input. This could give us a place to use CO2 from carbon capture.”

These caloric methods can also be harnessed for applications such as water heating or industrial heating.

“Now, it’s time for experimentation to test different combinations of materials and techniques to meet the engineering challenges,” Prasher said.

Lilley and Prasher have a provisional patent for the ionocaloric refrigeration cycle, and the technology is available for licensing.

- CategoriesIn SightGlass

- TagsSightGlass News Issue 28, solid state cooling