Pass the pub test on electric vehicles

- PostedPublished 21 April 2020

Talking to EV sceptics just got a lot easier thanks to VASA’s no-bull guide

The science on climate change is solid, but to help you steer the electric vehicle debate around this needlessly controversial subject, here is your cut-out-and-keep guide to counter several objections to electrified vehicles.

Calling BS on zero emissions

The EV marketing people really didn’t help themselves with that zero-emissions tagline. Zero tailpipe means zero tailpipe emissions, but what about the energy generation itself?

It could easily be argued that running an electric vehicle is just moving your tailpipe to the Latrobe valley or wherever coal is burnt to generate electricity in your state.

But at least your tailpipe isn’t in a densely populated area, reducing air quality for millions of people. From this perspective, electrification is a no-brainer.

Secondly, more and more coal-fired generation is being replaced by less polluting methods. Public charging networks tend to partner with renewable energy suppliers and surveys show a lot of EV owners naturally pair their purchase with home solar and/or connection to some form of clean energy tariff.

Let’s not forget the emissions intensity of getting petrol or diesel to your fuel tank in the first place, otherwise known as the fuel cycle.

A 2018 study by the International Council on Clean Transportation conducted calculated this alone to be 47 grams per kilometre for an average European combustion-engined car, compared with the European Union average of 44g/km to charge a 40kWh Nissan Leaf. And that’s before releasing emissions of any kind from the combustion engine’s exhaust.

Regardless, electric vehicles will only get cleaner as electricity generation moves away from fossil fuels.

Finally, energy security is a big issue for nations that rely heavily on imported petrol and diesel. Despite the International Energy Agency’s stipulated 90-day fuel reserve, in late 2019 Australia reportedly holds petrol and diesel reserves of just 18 days and 22 days respectively.

Australia narrowly avoided disastrous nationwide fuel shortages recently, as an escalation of tensions in Iran threatened to disrupt oil supplies during the peak of the bushfire crisis.

Even if Australians run their cars on electricity generated from burning coal, the energy security situation will be much improved, as will the air quality in cities.

The grid can’t handle it

First, our sadly diminishing heavy industry means reduced energy consumption and therefore free capacity.

Second, topping up an electric vehicle at home consumes around 7kWh when using a wallbox charger, about the same as running your air-conditioner, electric stove and oven all at once, as might be the case for many families on a summer evening. Also, EV owners tend to charge their cars later, to exploit off-peak tariffs.

Third, we don’t have enough petrol stations in the world for everyone to refuel at once, because we don’t.

Fourth, the EV transition isn’t going to happen overnight so there’s plenty of time to iron out any kinks in the grid.

Fifth, oil refineries use a heap of energy so reduced reliance on these will free up further capacity.

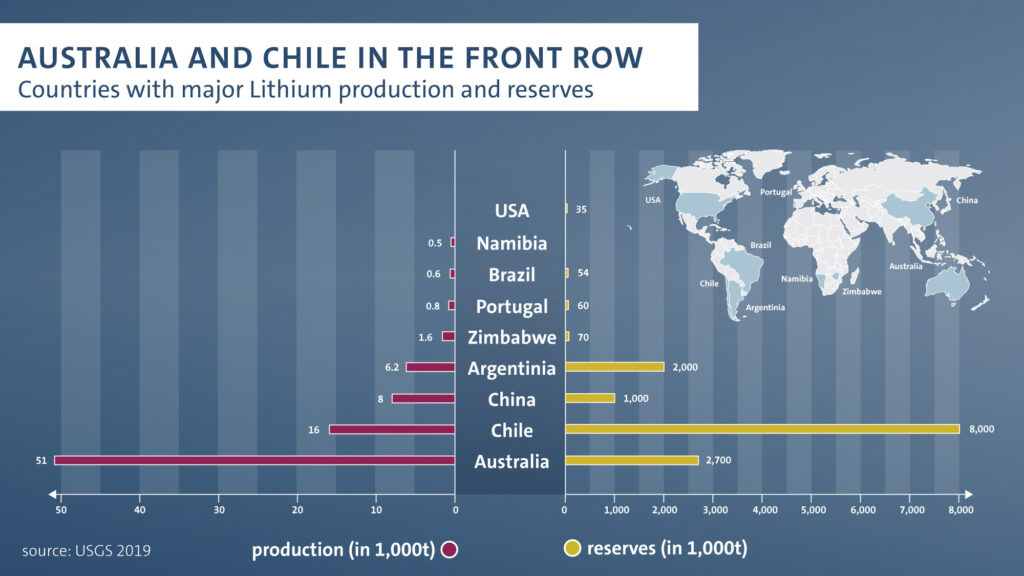

Lithium extraction is bad

So is oil exploration and extraction. Remember the Deepwater Horizon disaster of April 2010? Or the Exxon Valdez that wasn’t even in the top 50 largest oil spills but its location caused incredible environmental damage.

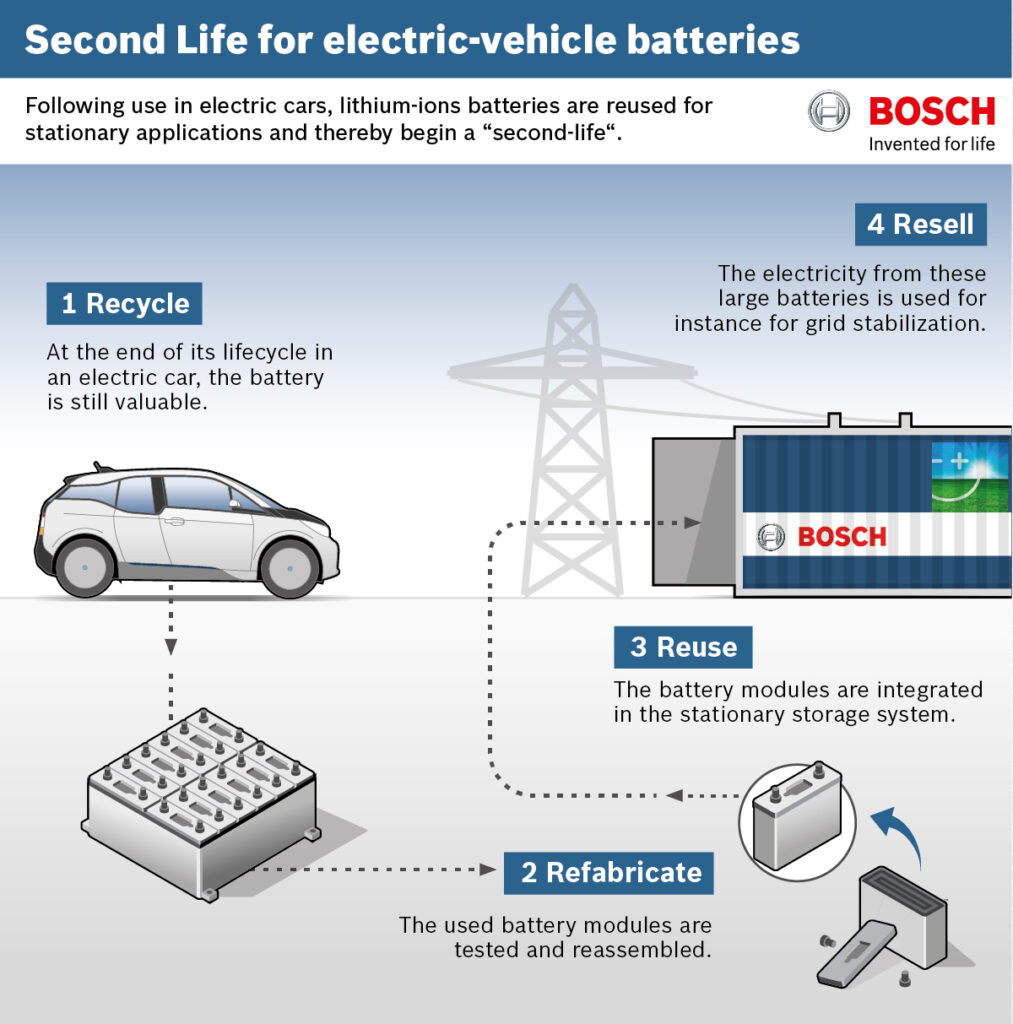

Unlike petrol, diesel and LPG that are gone forever once combusted, lithium has a long service life beyond EV batteries.

EV batteries are also proving longer-lived than originally expected due to intelligent cell balancing and thermal management.

Once a battery has reached the end of its service life in an EV, it remains more than adequate as home or grid energy storage for many years. After this, its components can still be recycled to give the nickel, copper, aluminium, lithium and cobalt an even longer lifespan.

Kids mining cobalt

Not forgetting the human rights records of several oil-rich nations and the use of cobalt in removing sulphur from petrol and diesel, this is a problem.

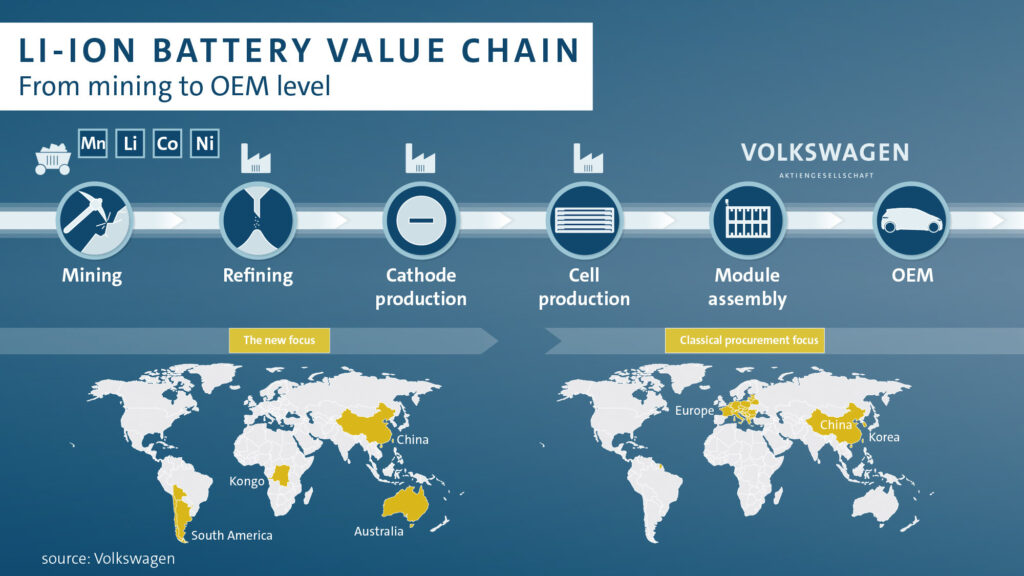

Some cobalt is illegally extracted by the children of around 150,000 impoverished families who live on the fringes of mines in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), a country that is anything but democratic and the source of almost two-thirds of the world’s industrial cobalt.

Attempts to supervise cobalt supply chains have proven difficult, implicating global technology giants such as Tesla, Apple, Google, Microsoft and Dell in a corruption-prone cobalt trade dominated by DRC and China.

Cobalt helps stabilise battery cells during recharging and researchers are working on eliminating it altogether.

Early lithium-ion batteries had cathodes comprising nickel, manganese and cobalt in roughly equal proportions but the latest battery chemistry has reduced cobalt to around 10 per cent of the total.

For example, the battery of an early Tesla Model S contained 11kg of cobalt, but the equivalent Model 3 contains 4.5kg.

The long service life and recyclability of lithium applies to cobalt as well, unlike petrol and diesel that also involve significant environmental and human risk – not to mention energy – prior to combustion.

Embedded emissions

The energy required and pollution created in the extraction and refinement (or recycling) of raw materials that go into a new vehicle is significant, as is the environmental footprint of manufacturing.

On the upside, many vehicle manufacturers are taking a holistic approach to EV production with a heavy focus on sustainability.

This includes the use of more recycled and natural materials in their construction, as well as ensuring more of the vehicle can be easily recycled at end-of-life.

There are several conflicting studies on the lifecycle environmental impact of EVs compared with their internal combustion equivalents, closely linked to how the electricity used to build the cars and charge their batteries is generated.

The aforementioned International Council on Clean Transportation study calculates the carbon footprint of manufacturing an average European vehicle to be 6.75 tonnes, compared with 5.7 tonnes for a Nissan Leaf plus another 4.05 tonnes for its 40kWh battery.

This means the Nissan’s embedded carbon is three tonnes higher than its combustion equivalent.

But given the average European combustion car’s tailpipe CO2 emissions of 165g/km, the Nissan would break even with the combustion model’s embedded carbon footprint within around 18,000km, based on the average electricity generation mix across the EU.

It takes too long to charge

We’re all accustomed to refuelling en-route, or even making a special journey to refuel.

Forget that, most EV owners charge at home or work and the average daily use of any private car is less than 50km, which can be recharged using a domestic socket in seven hours or three using the kind of 7kW wallbox often supplied with an EV.

Even big-battery EVs with a range of 400km and up can be rapid-charged in less than an hour, which is a reasonable duration to stop for a rest and a meal four hours into a long-distance journey.

In addition, destination chargers are more widespread than you’d imagine, making top-ups at regularly visited locations a cinch.

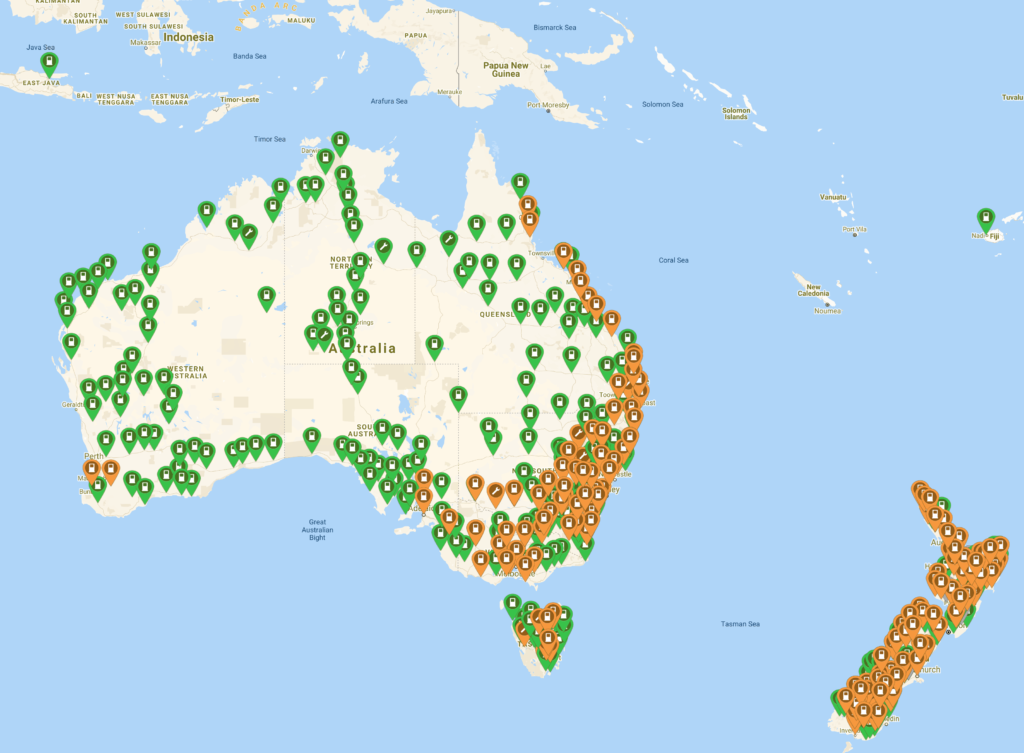

The infrastructure isn’t ready

It isn’t perfect but far more widespread than people who have never driven an EV would ever imagine, considering the tiny penetration of EVs in Australasia (see below screenshot from plugshare.com).

No off-street parking

That’s a tough one right now as it’s up to your local authority to install some infrastructure to enable kerbside charging, as is already commonplace in countries such as Norway where EV uptake is high.

You’ll just have to hold off on that plug-in purchase for a while. In the meantime, try lobbying your local MP, councillor and mayor to get some public chargers installed.

I live in an apartment

This is a similar scenario to those with no off-street parking, compounded by potential wiring capacity issues within the building.

Where there’s a will, there’s a way; the advice is to inform the landlord or strata authority that EV charging facilities are needed and why it’s a good idea, as the matter might not be on their radar.

Hydrogen is better

Firstly, it’s important to note that hydrogen fuel cell cars are still electric, they just have a range-extender fuelled by hydrogen.

Both battery electric and hydrogen fuel cell drive systems will each play important transport roles in future.

The easiest analogy to make is between petrol and diesel. Batteries, like petrol, are more suited to smaller vehicles and hydrogen could replace diesel in heavy-duty or long-distance applications such as haulage, rail and remote off-road travel.

As an energy storage medium, hydrogen is less efficient than batteries because it has to be extracted from fossil fuels (which defeats the purpose) or electrolysed from water (which is energy-intensive), then converted into electricity (a process that is only 60 per cent efficient).

Hydrogen also requires compressing or liquefying for storage and transportation, although the technology exists to produce it on-site at filling stations, which are still few and far between compared with public EV chargers.

Overall, it’s the filling station model that appeals, as well as the pure-water tailpipe emissions from a fuel cell and the potential to pipe hydrogen direct into premises as with natural gas today.

- CategoriesIn SightGlass

- Tagselectric vehicles, EV, SightGlass News Issue 19