CFCs on the rise again

- PostedPublished 11 October 2023

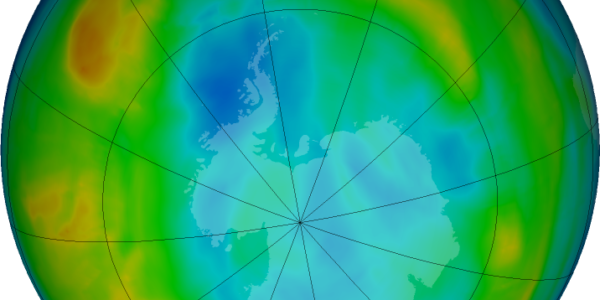

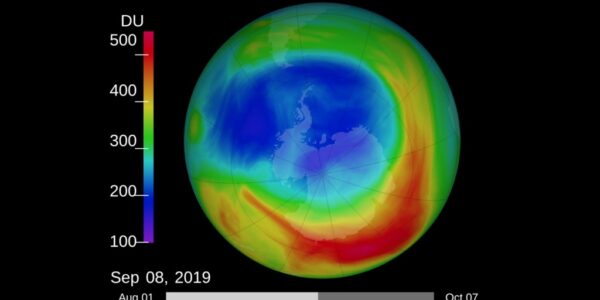

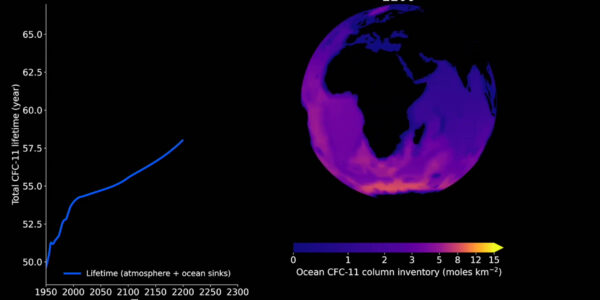

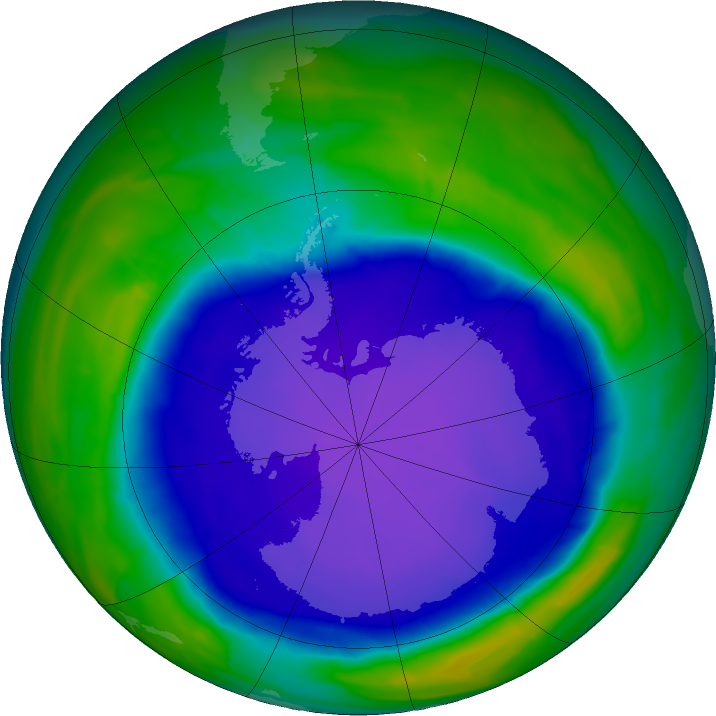

Banned since 2010, CFCs have surprisingly and rapidly increased in the Earth’s atmosphere this last decade. CFCs have an atmospheric lifetime of 52 to 640 years and act as powerful greenhouse gases that also destroy the ozone layer.

According to a recent study published in Nature Geoscience, the emissions of CFC-112a, CFC-13, CFC-113a, CFC-114a, and CFC-115 all rose, roughly equivalent to a small country’s total CO2 emissions.

Although banned under the Montreal Protocol, the most likely cause for three of the five CFCs, according to researchers, is a “loophole” that permits the production of CFCs while producing other chemicals, such as refrigerants and foam-blowing agents that are promoted as ozone-friendly CFC replacements, as well as potentially climate-friendly HFOs.

“We’re paying attention to these emissions now because of the success of the Montreal Protocol,” said Dr Luke Western, a research fellow at the University of Bristol and researcher at NOAA’s Global Monitoring Laboratory (GML).

“What we’re suggesting here is that there may be some cost to ozone and climate when creating these hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) and hydrofluoroolefins (HFOs), as ozone-depleting CFCs may be released during the process.” Dr Western said.

Three of the five CFCs found in the study, CFC-113a, CFC-114a, and CFC-115, are all required for the production of other compounds, including HFC refrigerants R134a and R125, which is one of the components in R410A. Their production has increased significantly since 2010.

The source of the remaining two CFCs found in the study, CFC-112a and CFC-13, is still unknown as they have no known legal uses. Factories in areas with weak regulatory frameworks are most likely the source of these prohibited compounds.

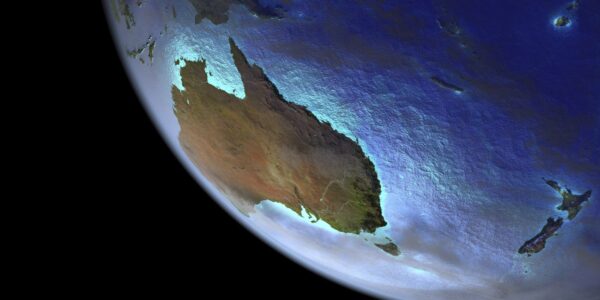

According to a 2019 study published in the Nature journal, when CFC-11 levels were discovered to be rising, scientists were able to identify the locations of the emissions across Asia with the help of frequent atmospheric monitoring stations. Eastern China accounted for around half of the rise caused by hidden CFC production, proving that global monitoring plays a key role in ensuring that climate obligations are met.

“CFC emissions from more widespread uses that are now banned have dropped to such low levels that emissions of CFCs from previously minor sources are more on our radar and under scrutiny,” said Dr Western.

The manufacturing process for CFC replacements is not entirely ozone-friendly, and it will take time for HFC and HFO substitutes that don’t produce CFCs as a byproduct to be adopted. If emissions continue to rise, however, this may offset some of the benefits that the Montreal Protocol has brought about.

The world’s major sources of CFC leakage continue to be abandoned appliances and construction foams, and while CFC levels are still less than five per cent of their historic highs in the 1980s, the Antarctic ozone hole is still expected to close by 2060.

- CategoriesIn SightGlass

- TagsCFCs, hcfcs, ozone, ozone layer, SightGlass News Issue 29