Decarbonising non-electrified railways with hydrogen trains

- PostedPublished 15 September 2021

In the European Union, according to train manufacturer Alstom, 46 per cent of mainline train tracks aren’t electrified.

As a result, many networks depend on diesel trains that can work on both electrified and non-electrified tracks.

While diesel trains are often considered environmentally friendly, if you compare their emissions per passenger kilometre to alternatives such as cars or air travel, the future emissions targets of many countries means that cleaner alternatives must be acquired.

Germany, for one, aims to reduce its carbon emissions by 65 per cent by 2030 – and it also intends to hit nearly net-zero emissions by 2045. Such objectives have subsequently prompted several companies and rail operators to explore the option of using electric trains powered by hydrogen fuel cells.

These trains, which don’t rely on an external source of power, offer a clean and potentially more sustainable alternative to diesel on non-electrified routes. They also offer increased range compared to battery-powered trains, and quicker turnaround times, making them more viable for some networks.

French rolling stock manufacturer Alstom, for example, introduced a train powered by a hydrogen fuel cell in 2018. The Coradia iLint, which has totted up more than 200,000km in passenger service since its introduction, is specifically designed for non-electrified lines and is reputed to offer good performance in conjunction with green operation.

Two iLints recently completed an 18-month trial in Lower Saxony, Germany, and the company has a significant number of orders on its books; 41 trains have reportedly already been purchased for use in the country, 12 are destined for France and Italy has earmarked six.

According to Alstom, the Coradia iLint has a capacity of 300 passengers, a range of 1000km and a top speed of 140km/h. Its roof-mounted tanks store hydrogen, which is used to drive a fuel cell and create electricity for the train’s traction motors. Energy can also be stored in lithium-ion batteries, for later use, and regenerative braking contributes to improved efficiency further.

Trials are also taking place in other countries, while companies such as the UK-based Eversholt Rail are collaborating with Alstom to develop new fuel-cell trains.

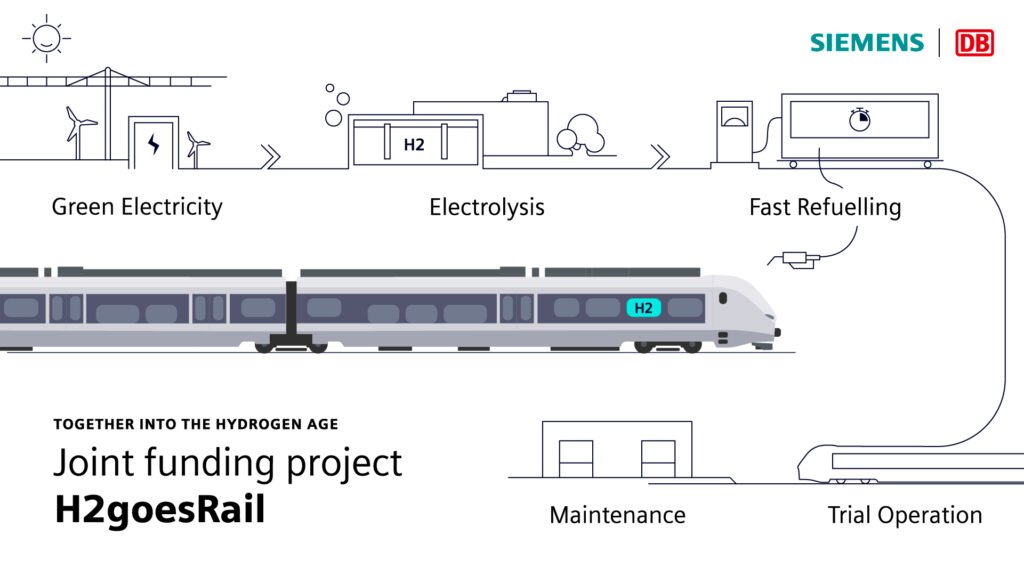

Rail operators Deutsche Bahn is also among those exploring the option of using electric trains equipped with hydrogen fuel cells; it has established a partnership with Siemens to test and develop a new hydrogen-powered train and the required infrastructure.

“We need to bring our fossil fuel consumption down to zero,” said Professor Sabina Jeschke, Deutsche Bahn’s board member for digitalisation and technology. “Only then can Deutsche Bahn be climate-neutral by 2050. By that point, we won’t have a single diesel-powered train operating in our fleet.”

Toyota trials hydrogen combustion engine

Although most hydrogen-related transport development is focused on its use in fuel cells, it can be used to fuel combustion engines, providing manufacturers with a clean, evocative and entertaining powertrain solution.

Toyota, which employs hydrogen in its fuel-cell Mirai sedan, has announced it is developing a hydrogen combustion engine for its Corolla Sport race car.

By employing hydrogen in a motorsport application, Toyota hopes to showcase the fuel’s capabilities and further the development of sustainable mobility.

The company says a hydrogen engine emits effectively no carbon dioxide, aside from that resulting from burning trace amounts of engine oil, while also offering improved response compared to a petrol engine due to quicker combustion rates. A hydrogen-fuelled engine also produce sounds and vibrations appealing to enthusiasts and motorsport fans.

While there are issues with hydrogen, including the potential environmental cost of its production, it could prove useful in certain markets or applications.

This is not a new idea, though, as BMW introduced a hydrogen-fuelled 7 Series in 2005. Only 100 were built, however, and problems included cost, complexity and fuel availability – all of which remain issues to this day.

Daimler and Volvo team up on hydrogen trucks

Daimler Trucks and the Volvo Group have announced a partnership to accelerate the use of hydrogen fuel cells in the haulage industry.

The new joint-venture is a fuel-cell systems business called Cellcentric, which is due to start assembling fuel cells in 2025.

Together, Daimler and Volvo will also call for the government support required to make hydrogen technology a viable and reliable commercial solution.

“Hydrogen-powered fuel-cell electric trucks will be key for enabling CO2-neutral transportation in the future,” said Martin Daum, chairman of the board of management of Daimler Truck and member of the board of management of Daimler.

“In combination with pure battery-electric drives, it enables us to offer our customers the best genuinely locally CO2-neutral vehicle options, depending on the application. Battery-electric trucks alone will not make this possible.”

While pure electric trucks have their uses in short- and mid-distance light haulage, the technology is not yet capable of meeting the demands of heavy-duty long-haul.

Consequently, developing and deploying hydrogen-based systems will potentially help more companies meet their decarbonisation targets.

Trucks using hydrogen-powered fuel cells will also benefit from advantages such as short turnaround times and performance that remains unaffected in colder climates.

Infrastructure and the green production of hydrogen remains a question mark but truck manufacturers and organisations, as well as Daimler and Volvo, are lobbying for the increased deployment of hydrogen refuelling stations – which, in conjunction with hydrogen-fuelled fleets, would help make road transport more sustainable.

More details on Cellcentric’s production facilities and plans will be announced in 2022. Prototype fuel cells are being developed and assembled and pre-series production will take place at a new site in Esslingen, in southern Germany.

Daimler and Volvo plan to commence independent customer trials in three years, with the subsequent independent series production of fuel-cell trucks following in the second half of the decade.

- CategoriesIn SightGlass

- TagsFCEV, fuel cell, H2, Hydrogen, hydrogen cars, hydrogen fuel cell, hydrogen internal combustion, hydrogen trains, hydrogen trucks, SightGlass News 24