Should Australia’s fuel efficiency standard give a free kick to gas guzzlers running R1234yf?

- PostedPublished 28 July 2023

In line with the recently released National Electric Vehicle Strategy (NEVS), the Australian Government has opened public consultations for the design and introduction of a fuel efficiency standard (FES) that will apply to passenger and light commercial vehicles – and the question of refrigerant global warming potential is included.

Australia, like Russia, is one of the very few developed countries without a fuel efficiency standard that penalises automotive manufacturers if the average CO2 emissions of all new vehicles sold in a 12-month period exceeds a required level.

Over the course of the year, in another round of public outreach, the FES consultation paper, in conjunction with NEVS, aims to ensure the best low-emissions and fuel-saving technology, such as that used in hybrid and electric vehicles as well as high-efficiency internal combustion engines, is sent to Australia by the global automotive manufacturers.

It is expected that, like in New Zealand, the Australian FES will work in a similar manner to the ‘European CO2 Emission Performance Standards’, where new passenger cars and light commercial vehicle manufacturers are incentivised directly to meet a given average CO2 per kilometre emissions target specified for that year.

Where a manufacturer exceeds this average, a penalty is imposed.

The EU also offers ‘off-cycle’ credits for eco-innovations that are approved and that reduce fuel use in settings outside of a formal laboratory test, such as high-efficiency vehicle lighting. A pooling arrangement, in line with EU rules, also exists, which allows higher-emitting vehicles to be offset from the sales of zero- and low-emission models from other brands within the pool; these can also be banked for future use.

If the status quo persists, Australia will continue to experience constraints in the supply of zero emission vehicles – reducing their accessibility and affordability, and manufacturers will continue to dispose of their highest polluting vehicles in our market.

ACT government submission to NEVS

Similarly, in the United States of America, Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards require manufacturers to meet a certain ‘miles per gallon’ average for their fleet of vehicles to avoid penalties, and in 2012, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) introduced a flexible credit system that rated vehicles on the global warming potential (GWP) of the refrigerant used in their air-conditioning systems.

Refrigerants can be powerful contributors to lifecycle emissions. However they are also separately addressed by the national phase-down of hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) gases; covering them in a vehicle standard may recognise non additional abatement.

Australian Industry Group submission to NEVS

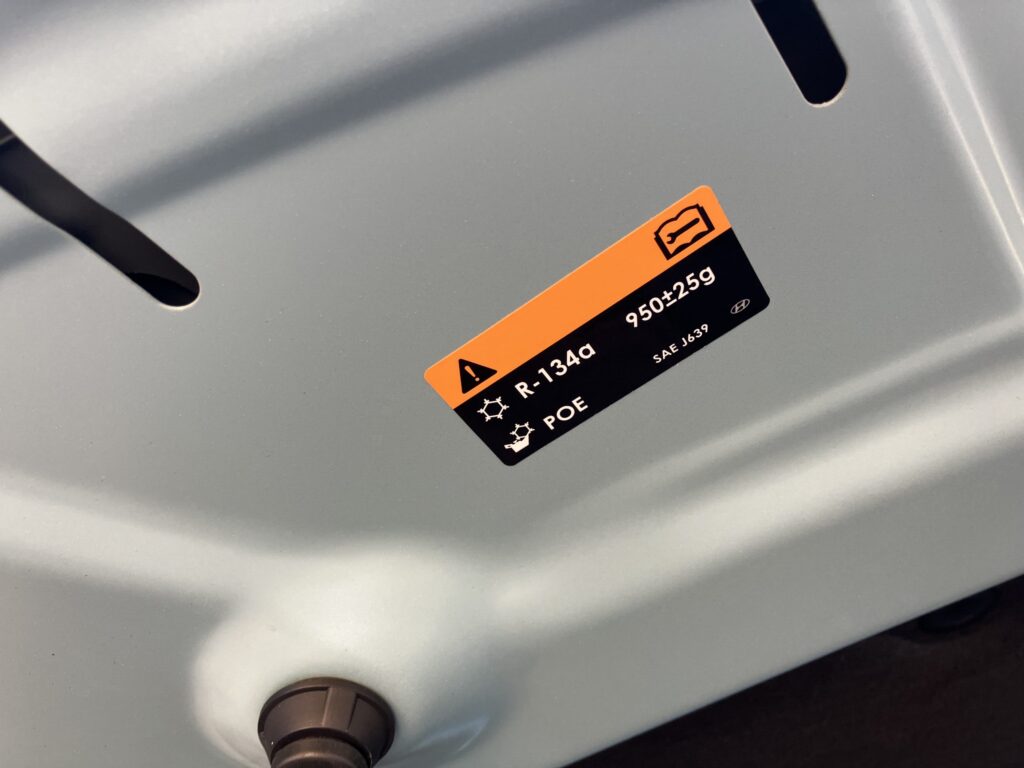

Manufacturers that transitioned early to R1234yf, which only lasts 11 days in the atmosphere, as opposed to R134a, which lasts 13 years, received credits under this system that could be used to offset sales of popular gas guzzlers in their CAFE accounting.

The current US fuel efficiency standards, adopted in December 2021, included credits for suppliers that exceeded the standard in a particular model year. Excess credits can also be bought from or sold to other suppliers to offset a shortfall, or they can be used to offset a shortfall in the previous three years or the subsequent five.

Australians lag the rest of the world when switching to cleaner cars, have fewer green options, and pay more per kilometre travelled as a result.

Setting an average carbon emissions limit for all new light vehicles sold by manufacturers that decreases over time is a top priority of FES.

Just like other fuel efficiency strategies implemented globally, the Australian FES paper is also looking into the possibility of bonus credits for the use of innovative powertrains. These include hydrogen as well as technologies that reduce a vehicle’s climate impact in real-world conditions that might not be captured in official lab tests, including the use of low-GWP air-conditioning refrigerants.

Australia presently relies on the Montreal Protocol (1987), the Ozone Protection and Synthetic Greenhouse Gas Management Act (1989), and the HFC phase-down (2016), yet it is believed that manufacturers have not been sufficiently encouraged to use low-GWP refrigerants in Australian-delivered vehicles.

Australia’s emissions ceiling should allow manufacturers some flexibility in how they meet their targets. This could be through allowing manufacturers who fail to meet their targets to purchase credits from manufacturers who overachieve, or through allowing overachieving manufacturers to accrue credits that they can use to meet targets in later years.

Grattan Institute submission to NEVS

Nonetheless, it is suggested that by awarding credits, their use would be accelerated ahead of the mandated HFC phase-down.

For others, it remains unclear if incorporating low-GWP refrigerants into the FES would make any difference, and even risk credits being handed out for something that would have happened regardless, instead of providing the Australian market with an increased availability of fuel-efficient vehicles.

That, or EVs will continue to be imported with a big charge of R134a onboard.

Regardless of how refrigerants end up being treated the Motor Trades Association of Australia (MTAA) cautioned that FES must not be overly aggressive in its initial design and introduction because this could jeopardise consumer choice and vehicle affordability.

“Government should not underestimate the importance of a well-planned and supported transition for employees across the automotive industry to ensure they can adapt and re-skill,” said MTAA interim CEO Geoff Gwilym.

He warned that otherwise “we could lose up to 20 per cent of small and medium enterprises”.

- CategoriesIn SightGlass

- TagsR1234yf, SightGlass News Issue 29