Global HFC phase-down progress

- PostedPublished 14 June 2015

There has been a lot of promising progress toward a global phase-down of HFCs under the Montreal Protocol in recent months, with just a couple of spanners in the works.

Many are hopeful that an international agreement will be forged his year with the Open-Ended Working Group of the Parties to the Montreal Protocol meeting in Paris scheduled for July 11-18 and followed by the Meeting of the Parties to the Montreal Protocol from November 1-5 in Dubai.

In fact the intention to form a contact group at the Paris meeting is thought to indicate that formal negotiations will begin this year – a very positive sign.

A majority of developing and developed countries now support an HFC phase-down under the Montreal Protocol – but the UN estimates the cost to developing countries could be more than $US3 billion and only $US500 million has so far been pledged by the developed nations.

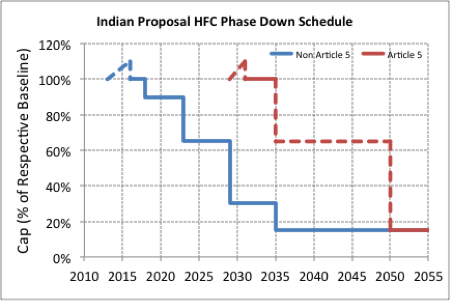

One of the most significant developments has been India’s back-down from its hard-line opposition to phasing down HFCs under the Montreal protocol and coming to the negotiating table with a proposed amendment.

India’s proposal would give developing countries until 2031 to freeze HFC production and consumption at baseline levels established between 2028 and 2030, with a 15 per cent reductio by 2050.

It remains a big step away from the United States’ proposal but India insists its domestic industry needs time to adopt technologies that both reduce environmental impact and are suited to the subcontinent’s high ambient conditions.

As a caveat, India insisted its adherence to the phase-down would depend on insisted that the phase down of the HFCs depends on “flexibilities in terms of choice of alternative technologies and timeframe for transitioning to safe, technically proven, energy-efficient and economically and commercially viable technologies”.

India also wants full compensation for the 150 or so developing (Article 5 in Montreal Protocol parlance) countries, including for lost profits caused by the closure of HFC production facilities and technology conversion costs.

The European Union has also submitted a phase-down proposal that could reduce opposition from developing countries, but it is far stricter than India’s and puts even more onus on developed nations to take the lead.

Under the EU proposal, developed (non-Article 5) countries would have their phase-down more closely aligned with Europe’s ambitious “F-Gas” regulations.

A baseline of HFC production and consumption from 2009 to 2012 would be set, plus 45 per cent of the ozone-depleting HCFC consumption permitted under the Montreal Protocol in the same timeframe. Figures will be expressed in CO2 equivalent rather than volume.

In 2019 the baseline would be reduced to 85 per cent, followed by reductions to 60 per cent in 2023, 30 per cent in 2028 and 15 per cent in 2034.

Meanwhile Article 5 would have different allowances for production and consumption, while taking into consideration the allowances for HCFC production that have only just started to be phased out in developing nations.

Again a CO2 equivalent baseline figure calculated between 2009 and 2012 will be used, but only applied to production and a more generous 70 per cent figure for HCFCs will be applied.

The EU proposes these countries freeze HFC production by 2019 and take steps to achieve 15 per cent of that amount by 2040, with the timetable of steps agreed by 2020.

For consumption, the baseline is proposed to be the combined average CO2 equivalent of HFC and HCFC consumption between 2015 and 2016, with a freeze n the consumption of both by 2019 and a reduction scheme to be agreed the following year.

The new proposals have injected fresh energy to the negotiations, with the African group now voicing support for bringing HFCs under control and getting the minority of resisting countries on-board.

Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states have maintained stubborn opposition to an HFC phase-down, based on the opinion that new technology options remain unavailable or unviable for markets in which comfort cooling is vital.

However Saudi Arabia is reportedly among the nations agreeing to discuss the establishment of the contact group at Paris, which should herald the initiation of formal negotiations.

Getting everyone to agree will not be easy, but it has been done before and the ozone layer is recovering as a result.

US HFC phase-down hurdles

While the world grapples with how to enact a global HFC phase-down, the United States is having its own internal dramas.

Congressman Ed Whitfield, who chairs the influential Energy and Power Subcommittee, has written to the Environmental Protection Agency voicing his concerns about proposals to ban certain uses of common high global warming potential (GWP) refrigerants including R134a, R404A and R507A, from as early as the beginning of next year.

A number of equipment manufacturers have also warned that meeting the deadlines would be almost impossible, expensive and risk the safety implications through the use of potentially unsuitable alternatives such as flammables.

“I understand the consensus among the affected companies in the refrigeration, motor vehicle, and insulation industries is that the proposed compliance requirements are not feasible, would cause considerable economic harm and job losses, and may increase rather than reduce risks to the American public,” wrote Congressman Whitfield.

He also pointed out some conflicts with the Department of Energy’s new efficiency standards, which will apply to domestic and commercial refrigerators from 2017 and specify the use of come of the same HFCs targeted by the EPA as foam-blowing agents and refrigerants due to their energy efficiency advantages.

“EPA and DOE have apparently made no attempt to coordinate the implementation deadlines of rules affecting the same products.”

Meanwhile, Emerson Climate Technologies Vice President Rajan Rajendran raised similar concern and recommended the phase-out schedule of prominent high-GWP refrigerants to be extended by five or six years and that the EPA and DOE coordinate their regulatory initiatives so that industry has a single deadline to work towards.

“If the current proposal on refrigerants becomes the final rule, OEMs will have all of six months to get new equipment and retrofit components ready for the 2016 EPA deadline. Right after which the equipment makers will have to work to meet the new higher efficiencies mandated by the DOE,” said Dr Rajendran.

On a more positive note, the US Defence Department, General Services Administration and NASA are all proposing to update Federal Acquisition Regulations so that they force the procurement of low-GWP refrigerants.

This includes the purchase low-GWP alternatives to HFCs where feasible and the transition to equipment running on safer, more sustainable alternatives.

If approved, the regulation changes would require contractors to reduce HFC emissions and where feasible, use low-GWP alternatives as part of regular equipment maintenance and replacement.

Government contractors would also have to report the amount of HFCs or HFC blends in equipment with charge weights of around 23kg or above delivered to the government, plus the amount of HFCs and HFC blends used or recovered as part of the installation, service or disposal process.

- CategoriesIn SightGlass

- TagsHFC phase down, Kigali Amendment, Montreal Protocol, SightGlass News Issue 2