VASA presidents reflect on the association’s first 30 years

- PostedPublished 17 October 2023

Brett Meads (2022-present)

As VASA celebrates its 30th anniversary this year, it’s quite an interesting exercise to reflect on just how much change our industry has undergone, and how those changes have influenced the professionalism of those working on the humble motor car.

While 1993 saw the official birth of VASA as an industry association, it was in 1992 that ideas were discussed and momentum was gained.

There were lots of drivers for this, all well documented over the years, primarily to provide an intelligent industry voice to government, and to encourage an acceptance of professional development, industry training, and best practice workmanship.

Importantly, we needed to do better by the environment, now that we had compelling science that could quantify the impact of releasing the refrigerants of the day to the atmosphere.

I was busy in 1992, getting my hands dirty installing and repairing car AC systems in a hot and humid South East Queensland. I was driving a current model Holden VP Commodore SS, which was reasonably flash in the day. Sure, it wasn’t a Calais, or a Benz, or a Cressida, but it had a five litre port fuel-injected V8 and fuel was cheap.

There were no airbags, no lane departure, no ADAS, no CarPlay, and no push-button start.

The SS didn’t get climate control, and without ticking the power-pack option, you had to wind your own windows. The air conditioner was single zone, with a mechanical thermostat, and ran on CFC-12 refrigerant.

It wasn’t until 1993 that we saw a Commodore with R134a refrigerant, a single driver-only air bag, and an automatic transmission with primitive electronic control.

In fact, 1993 heralded the VR Commodore, the ED Falcon, and the Wide-Body XV10 series Camry, all released with R134a refrigerant. As Dylan observed, for the times they are a-changin’.

In 2023 you can’t buy a new Holden. If you had told us that 30 years ago you would have been laughed at or invited outside to settle the matter.

Importantly, this year finds our industry in the middle of another refrigerant transition, to R1234yf, and for good reason.

As we see low GWP refrigerants become commonplace, so too is radar-cruise, adaptive suspension, electric steering, autonomous braking, driver attention monitoring, and crash avoidance, just to name a few. Heady stuff when you consider we had none of these technologies not that long ago.

If you graph the rate of technological change in the automotive industry over the last 30 years, the climb is astonishing. However, it is nothing compared to what tomorrow will bring.

The drivers for change today are as prominent and important as they were 30 years ago.

As an industry we need to continue to share knowledge, have a voice in the regulatory debate, carry out best-practice workmanship, and do the right thing by the environment.

The last 30 years have been one hell of a ride. We have become a smart, resilient, and technologically intelligent industry.

Which is exactly what we need to be to embrace the opportunities offered by the next 30 years.

To say there are exciting times ahead in the automotive thermal management and electrical space would be the understatement of the century. What a fantastic industry to be a part of.

Ian Stangroome (2009-2022)

Vehicle air conditioning has come a long way since its invention in the 1930s. What once might have been considered an optional extravagant luxury has, for the better part of the last 20 -25 years, become not just a standard feature in a vehicle, but essential for occupant comfort and safety.

VASA was first incorporated in 1993, its membership dedicated specialists in every aspect of mobile air conditioning and represents 30 years as a major player in this sector throughout Australia and New Zealand.

While VASA’s history falls significantly short of the more than 90 years since the invention of the vehicle air conditioning system, it is underpinned by the accumulated experience and knowledge of the many individuals operating in the MAC space in our region.

Many of those individuals have been recognized and awarded by VASA over the years, not only for cooling and heating vehicle passenger compartments when no others could or would, but also for their contribution in creating and developing an industry which simply did not exist.

As we celebrate and reflect on VASA’s 30-year involvement in the sector, it should not be forgotten that, prior to VASA, those individuals had no access to industry training or support and certainly did not enjoy the benefits of the internet which we have all come to rely upon for information and communication.

Instead, they garnered whatever information they could from overseas sources and when that was not available or forthcoming, dug deep into their own ingenuity and other limited resources to produce amazing results for their customers and build lasting reputations.

I first heard of the possibility of forming an industry association for the MAC sector through one of my key suppliers and subsequent Director of VASA’s inaugural board, Glen Watkinson.

I immediately thought “it was not just a great idea, but something lacking and desperately needed”.

For a number of years, we had been hearing about a hole in the ozone layer, the formation of which was attributed to the release of the refrigerants we were using. When VASA was rolled out, I was one of the first to apply for membership.

Our industry was about to change. State based Environmental Protection Authority, or their equivalent in each state, introduced licensing for all those who had a desire to continue working with refrigerants.

We were required to undertake training to understand the ozone problem as a requisite for licensing. The perfect refrigerant R12, which we had used reliably since the inception of vehicle air conditioning, was now targeted as a major issue and had to go.

A new refrigerant was now available, R134a. All new vehicles in Australia after January 1995 were to use R134a. We now had two refrigerants to work with.

But wait, there’s more. 5GS mineral oil used in all R12 automotive systems was not suitable in a R134a system and was to be primarily replaced with a Poly Alkylene Glycol (PAG) or Polyol Ester oil. Only two new oils, but a multitude of viscosity grades. So, essentially many new oils to consider.

A system retrofit program for all popular vehicle models was rolled out. For the industry there was much to consider.

Training on the new refrigerant; training on retrofitting systems; they have also banned R11, how do we now flush a system? How do we get all the mineral oil out and replace it with an alternative? Which alternative? How much oil contamination is too much? We need recovery equipment, what do we buy? Do we recycle and reuse R12? (Servicing of existing R12 systems was never banned). R134a is expensive, do we recycle that as well?

Vehicle air conditioning systems were now becoming integral components of the vehicle. We rarely installed an under-dash evaporator which saw the death of the simple electrical circuit consisting of a fan switch, a mechanical thermostat and a electromagnetic compressor clutch coil.

We were starting to see electronic thermostats, pressure switches became mandatory, which evolved into pressure transducers.

Relays were included to incorporate condenser and radiator fans in the function of the air conditioner.

Electronic fuel injection was already on the scene and subsequent electronic control of the air conditioner through ECUs became the norm.

Manual air conditioning became automatic, and then single zone became dual, then tri, quad and multi.

Where were mechanics, auto electricians and vehicle air conditioning specialists going to get the answers to all these emerging changes and their inevitable questions.

It would have been a very different journey through all these changes had VASA not been formed.

VASA, through its communications within Hot Air, then SightGlass News and now simply SightGlass, and the Registered Training Program are able to provide many of the answers.

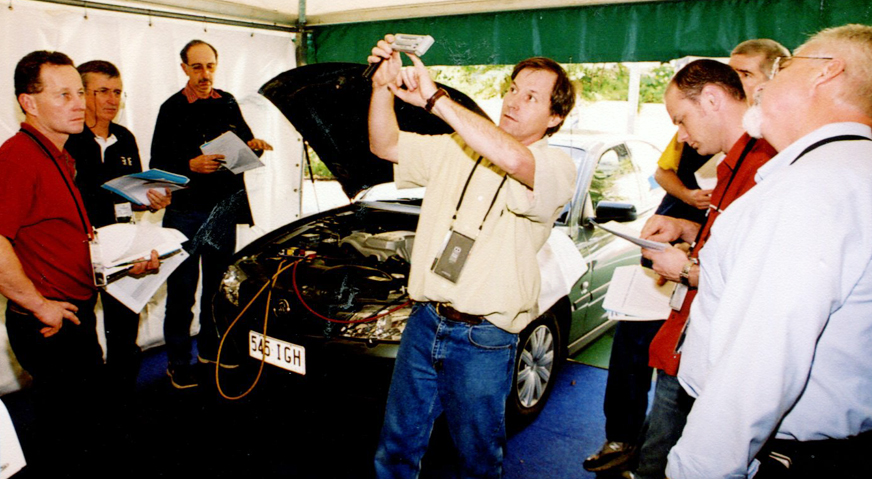

VASA provides training opportunities, both standalone training sessions as well as its now popular and well supported conventions which also presents delegates with opportunities to grow their individual networks, further enhancing their problem-solving capabilities.

In 2006 VASA incorporated the Automotive Electricians Association which not only further enhanced the network, but also helped to fill many of the knowledge gaps as the challenges relating to the implementation of more and more electronic control into vehicles systems really began to bite.

VASA has grown to become a significant industry stakeholder and participant and retains Board representation on the Australian Refrigeration Council (ARC) and Refrigerant Reclaim Australia.

VASA is affiliated with MACS in the United States and MACPartners in Europe providing global insight to what is likely to be coming our way. VASA is acknowledged as a co-contributor to The Australian Automotive Air Conditioning Code of Practice.

Everyone is well aware that technology in vehicles is increasing exponentially with the uptake of electric vehicles and increasing autonomy.

We also have another change of refrigerant to contend with as we make the slow but certain transition to R1234yf in new vehicles.

VASA has been on top of providing training and information in that regard for many of years in a number of formats including that of the Future Gas seminars.

Vehicle air conditioning is no longer solely dedicated to passenger compartment comfort but must also meet the requirements for thermal management of EV batteries and associated equipment. Hence the need for ongoing specialised training and development is not going to diminish any time soon but more so has to keep pace at a minimum.

As time marches on, the challenges do not become any less, but we should trust that our ability to meet those challenges improves.

It would be my hope that VASA continues to grow and play a major role in that.

Mark Padwick (2004-2009)

Mark Padwick, who was involved with the movement that became VASA from well before its inception and served as president from 2004 to 2009, discusses the formative years of what was originally known as Vehicle Air Conditioning Specialists of Australia.

“It would have been around the late 1980s, early 1990s,” he recalled.

“A group of us working in the sector at the time realised there were some big changes coming down the pipeline with refrigerants and regulations. We needed to establish some industry standards, codes of practice, and qualifications framework to help guide everyone.”

Mark explained the catalyst was the phasing out of ozone-depleting CFC refrigerants and a switch to R134a was on the horizon. Meanwhile, the licensing and certification regime to work with refrigerants was still in its infancy.

“Back then, there were definitely some ‘cowboy operators’ as we used to call them,” he said. “Skill levels varied wildly and there wasn’t much in the way of formal training available.”

It was clear to Mark and his colleagues that the industry required coordination and leadership to navigate these changes smoothly. But forming an association had its own challenges.

“We had to determine what type of qualifications would be needed going forward and how to bring all parts of the industry and relevant government bodies under the same umbrella,” Mark noted.

Bringing disparate stakeholders together proved difficult in those early days. But eventually VASA was established, with Mark playing an active role from the start. He was later elected president, a role he served from 2004-2009. During his tenure, a major focus was on training and skills development.

“We realised licensing would soon require proper qualifications to work on vehicle air-conditioning systems, so we put a lot of effort into developing training courses and raising competency standards across the board,” Mark explained.

Examining how the industry has changed, Mark observed that specialisation has declined significantly.

“Back when VASA began, you still had dedicated air-conditioning companies. But now it’s almost a generalist trade. I’d be surprised if there were more than a handful who only do air-con work,” he said.

This trend developed as factory-fitted air conditioning became the norm and decimated demand for aftermarket installations. It pushed firms to take on mechanical and electrical tasks too. In recognition of these converging skill sets, VASA merged with the Australian Association of Automotive Electricians in 2005. According to Mark, this helped guide members through major industry shifts.

Reflecting on VASA’s impact and legacy, a sense of pride was evident as Mark stated: “During my time in particular, I believe we really lifted the professionalism of the whole sector.”

When pressed on his proudest achievement, Mark didn’t hesitate: “Improving standards across the board. If you had to pick one thing, that would be it for me.”

Mark Padwick credited several figures people as influential in the development of VASA and the local auto-AC industry:

- Mark Mitchell: Padwick described Mitchell as a driving force behind the formation of VASA. Mitchell served as VASA’s first President for 10 years before Padwick took over the role.

- Norman Bilton: Padwick said he, Mark Mitchell, and Norman were among the initial group discussing the need for an industry association in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

- Ralph Cadman: Padwick listed Cadman as one of the inaugural directors on VASA’s board alongside himself, Mitchell, and John Blanchard.

- Steve Pohlner: Pohlner’s involvement was as a Ford Australia engineer who began opening lines of communication between car-makers and the aftermarket sector. Padwick’s role at Sanden, which supplied compressors to Ford, was key to this relationship. As well as presenting at VASA events on multiple occasions, Pohlner facilitated a tour of some facilities at the Ford Australia proving ground for a Wire & Gas conference.

Mark Mitchell (1993-1999)

Founding VASA president Mark Mitchell played a key role in establishing recognition for automotive air-conditioning technicians and among his pivotal roles over the decades, was key to the formation of both VASA and what is now known as the Australian Refrigeration Council (ARC).

“Back in the late 80s and early 90s, there was a real push to restrict who could work on vehicle air-conditioning systems,” Mr Mitchell recalled about the upheaval around switching from ozone-depleting CFC R12 to less environmentally damaging R134a.

Other industry groups wanted to limit repairs only to refrigeration mechanics while some in the automotive industry downplayed the specialist skill and knowledge required to work on automotive AC systems, suggesting it was as simple as changing a tyre, which would shut out the many independent automotive air-conditioning technicians and businesses at the time.

Mitchell fought against these efforts as a director of MTAQ but faced strong opposition from powerful commercial interests. “I could see across the boardroom table that I was fighting a losing battle,” he said. Mitchell resigned in protest and immediately started organising the industry to stand up for themselves.

Within days, Mitchell had convened a meeting of industry players on the path to establishing what would become VASA.

In September 1993 Around 90 people turned up to a summit held at the Marriott hotel in Surfers Paradise – that has since held numerous VASA Wire & Gas events – showing the level of concern within the industry.

“All the traditional cool mavericks that invented the industry were still working at the time. The idea that they couldn’t touch a car anymore was just outrageous,” Mitchell explained.

Establishing recognition for automotive air-conditioning technicians as a distinct and skilled group was a major challenge. Mitchell spent years lobbying state and federal governments to help them understand the identity and capabilities of the industry.

He helped develop the first Code of Practice – despite sneaky moves from other automotive industry bodies to claim the funding and credit for doing so – and played a key role in establishing training and certification requirements.

Once VASA was up and running – with 84 members in its first year, of which several remain so three decades later – the organisation fought other battles too, such as against the use of hydrocarbon refrigerants in motor vehicles.

Mitchell and others faced defamation lawsuits but the cases were dropped once VASA hired Australia’s top consumer trading and trades practices barrister.

For the next decade VASA focused on improving training standards and working with regulators.

However, Mitchell expressed disappointment that similar issues resurfaced during debates around greenhouse gas regulations as R134a began to make way for low-GWP products such as R1234yf.

While pleased that the ARC was formed, it did not achieve the government-endorsed industry-owned, competency-based licensing structure Mitchell envisioned and would have been more future-proof for today’s shift away from synthetic greenhouse gas refrigerants.

Looking ahead, Mitchell sees many parallels with the shift to electric vehicles. “History is repeating itself as other trades try to claim the work. But we can’t shut out the existing skills and experience,” he argued, referring to some stationary electricians’ groups saying they should be the ones to work on EVs rather than those originating in the auto sector.

Proper DC voltage safety training will be crucial while EV thermal management systems require a sound understanding of refrigeration fundamentals.

Overall, Mitchell is proud of the VASA’s role in securing the automotive air-conditioning industry’s future in Australasia.

And although he has now stepped down from the VASA board, he remains committed to doing whatever he can to ensure technicians can continue adapting to new technologies like electric vehicles.

Mark Mitchell mentioned several other industry figures who played important roles in the early days of VASA:

- Chris Lindeman who Mitchell said he had a pivotal discussion with in a hotel room about needing to take a stand against the restrictions being proposed.

- Steve Anderson from Refrigerants Australia, in conjunction with the team from the South Australian EPA, who Mitchell said helped with most of the heavy lobbying and writing of the first Code of Practice draft, and who just kept going despite opposition from other groups.

- Ralph Cadman who Mitchell named as one of the original directors when VASA was formed along with John Blanchard.

- Jeff Smit who Mitchell credited with a passion for training and his role in helping establish The Automotive Technician (TaT). Smit also played a role in debates around greenhouse gas regulations and training.

- Robert Burns from Nippon Denso who Mitchell said provided helpful input during revisions to the Code of Practice.

- Johnny Wallace who he recalled contacting along with Ralph Cadman and Chris Lindeman shortly after resigning from the MTAQ to start organising the industry.

- Frank Burgess of the IAME, who made a gaffe at a national training meeting that inadvertently helped Mitchell’s argument that auto-AC technicians were qualified to do the work.

- Grant Hand who developed the Registered Technicians Program, thought to be Australia’s first training tool of its kind for automotive air-conditioning technicians.

- Alan Woodhouse and Kevin O’Shea, who Mitchell named as among the loud voices pushing for the formation of the National Refrigeration and Air Conditioning Council (which became the ARC).

- Tom Brennan the barrister VASA signed up to defend Steve Anderson against defamation lawsuits from hydrocarbon suppliers and the appointment of whom Mitchell said was instrumental in getting the charges dropped.

- CategoriesIn SightGlass

- TagsAnniversary, Brett Meads, Ian Stangroome, Mark Mitchell, Mark Padwick, SightGlass News Issue 30, VASA